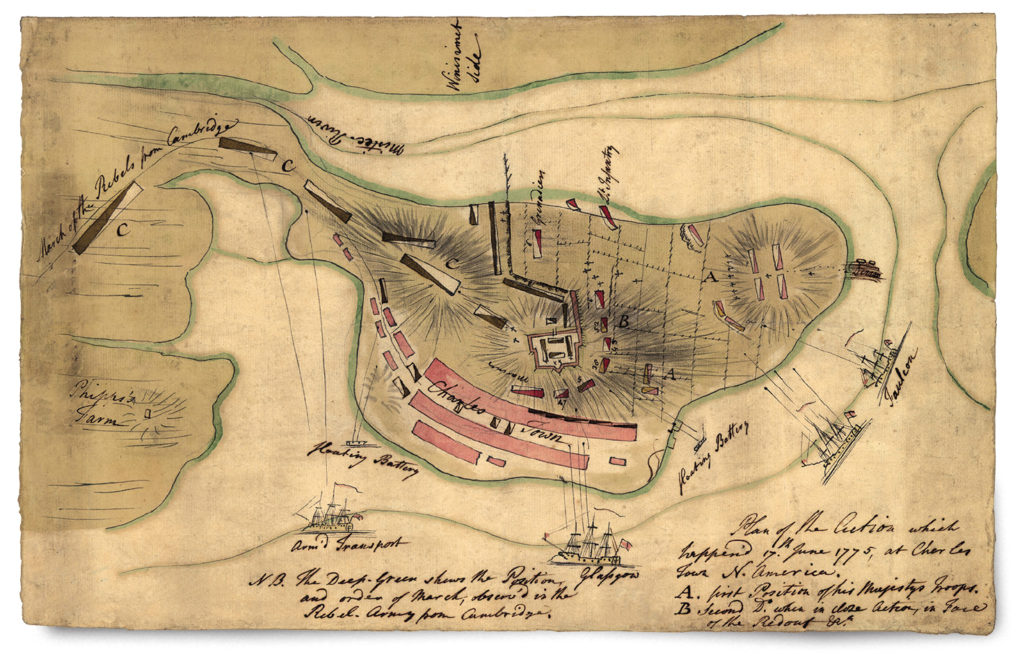

On June 17, 1775, a vicious battle rocked Bunker Hill in Charlestown, Mass. That first major engagement of the Revolution saw British Commander in Chief William Howe lead around 2,000 Regulars in what Howe expected to be a quick victory over 1,200 colonists commanded by Colonel William Prescott. Howe guessed wrong. The fierce, bloody fighting raged through the night. From a hillside miles away, Abigail Adams, 30, and son John Quincy, 7, watched with excitement and anxiety.

The Adams family lived in Braintree, a small coastal town 12 miles south of Boston. Abigail’s husband, John, a lawyer and key figure in the insurrection, had been gone since April, when he left on a meandering journey, eventually arriving in Philadelphia to attend the Second Continental Congress that convened May 10. John’s departure began a long separation that left Abigail Adams and their four children in one of the most dangerous places on earth—a city under siege—for nearly two years. She would have to run the family farm, keep her children safe, and husband the family’s finances. Abigail’s letters to John during this time, some of the most reliable accounts of significant early events in the Revolution, influenced decisions being made in Philadelphia that shaped the nation.

John Adams and Abigail Smith met in 1759. He was 25, living with his parents in Braintree; she was 15, also at living at home in Weymouth, just to the south. Writing was the easiest way to communicate, and when they began courting in 1764, the two established themselves as exuberant letter writers. Honest, poetic, tragic, joyful, and deeply thoughtful letters flew back and forth between the young romantics. He nicknamed her “Portia,” for the independent-minded heroine of The Merchant of Venice, and that was how she signed some letters. The couple married on October 25, 1764, when John was 29 and Abigail 19. They welcomed their first child, Abigail—nicknamed “Nabby”—the following year. By the time John left for Philadelphia in April 1775, John Quincy, Thomas, and Charles had arrived.

Like her husband, Abigail firmly believed in the American experiment and staunchly opposed slavery. She relished the Boston Tea Party. After Lexington and Concord in April 1775, she wrote to John and many friends and acquaintances, expressing joy and anxiety. In a letter to rebellious Plymouth playwright Mercy Otis Warren, Abigail described her emotions following the fighting. “What a scene has opened upon us since I had the favor of your last!” she wrote May 2. “Such a scene as we never before experienced, and could scarcely form an idea of. If we look back we are amazed at what is past, if we look forward we must shudder at the view.”

Rebel Bostonians, having stepped collectively into the unknown, feared for their future. Abigail found a tonic for unease in her excitement at seeing the patriotism she had long advocated taking root and spreading. “Our only comfort lies in the justice of our cause,” she wrote. She urged Mercy not to leave Plymouth for relative safety inland, adding, with the characteristic vehemence that often outdid her husband’s: “Britain Britain how is thy glory vanished—how are thy annals stained with the Blood of thy children.”

As Abigail was writing to Mercy, John, now in Hartford, Conn., was writing to Abigail. He knew that in wartime even agrarian Braintree was bound to suffer. “Our hearts are bleeding for the poor People of Boston,” he wrote May 2. “What will, or can be done for them I can’t conceive. God preserve them.”

In that letter, John told Abigail he had purchased books on military strategy and said that if his brothers were interested, he’d be able to train them to be officers. “Pray [sic] write to me, and get all my friends to write and let me be informed of every thing that occurs,” he wrote.

Abigail took his request seriously. In a lengthy May 24 letter, she recounted an incident in Weymouth the previous Sunday morning. She awoke at 6:00 and learned the Weymouth bell had been ringing, that cannoneers there had fired three shots to sound an alarm, and that drums had been beating. Abigail hurried the three miles to her hometown and found everyone, even physician Cotton Tufts, “in confusion.” She described a wild scene, the result of four British boats anchoring within sight of Weymouth Harbor.

According to Abigail, a rumor had spread that 300 Redcoats had landed and were about to march through town. Residents began scrambling to fight or run. Abigail’s family fled. “My father’s family flying, the Dr. in great distress, as you may well imagine,” she wrote, “for my aunt had her bed thrown into a cart, into which she got herself, and ordered the boy to drive her off to Bridgewater which he did.”

Abigail was describing the “Grape Island Incident.” According to her letter, 2,000 local men gathered to fight, but the British never sent troops ashore. Instead, on Grape Island, a minor land mass in Boston Harbor, they stocked a barn with hay. The Weymouth men procured a small boat, intending to torch barn and contents. “We expect soon to be in continual alarms, till something decisive takes place,” Abigail wrote.

Though not decisive, Bunker Hill was a British victory, earned at great human cost and a boost to patriot morale because neophyte freedom fighters had stood their ground and were not overrun. The battle personally touched Abigail and John. Their good friend and physician Joseph Warren (no relation to Mercy) had died in action. “God is a refuge for us.—Charlestown is laid in ashes,” Abigail wrote to John on June 18. “The Battle began upon our intrenchments upon Bunkers [sic] Hill, a Saturday morning about 3 o’clock and has not ceased yet and tis now 3 o’clock Sabbeth [sic] afternoon.”

In a passage of the same letter written June 20, Abigail lamented her inability to gather quality intelligence for John about the battle. “I have been so much agitated that I have not been able to write since Sabbeth day,” she wrote. “When I say that ten thousand reports are passing vague and uncertain as the wind I believe I speak the Truth. I am not able to give you any authentic account of last Saturday, but you will not be destitute of intelligence.”

In reality, Abigail had a knack for threshing fact from fiction—over the years she heard many rumors of John’s death by all manners, including poisoning, but never believed any. Regarding Bunker Hill, she was able to assemble and recount a reasonably detailed narrative of events there, and she assured John that news of Warren’s death was true.

On the same day as the battle, George Washington was named commander in chief of the Continental Army. He rushed to Boston, intent on forcing the British to evacuate. Abigail first met him July 15, 1775, less than a month after Bunker Hill, with the city still under massive financial and military stress. The next day, she wrote that the appointments of Washington and General Charles Lee to positions of command had given locals “universal satisfaction,” but she also pointed out that the people would support leaders only as long as they were delivering “favorable events.” Washington displayed “dignity with ease, and complacency, the gentleman and soldier look agreeably blended in him,” Abigail wrote. “Modesty marks every line and feature of his face.” By the time that note would have reached John, he was going through a grave embarrassment—one threatening both his budding political career and worldwide geopolitics.

In the summer of 1775, many members of Congress believed war with Britain was still avoidable. On July 8, Congress signed the “Olive Branch Petition.” Written by John Dickinson, a Pennsylvania delegate, the document was a final reach for peace. That outcome was a long shot, but the British intercepted an inflammatory July 24 letter from John Adams to Colonel James Warren, Mercy’s husband. In that communique, Adams suggested to Warren that by now the colonists should have “completely modeled a constitution,” “raised a naval power and opened all our ports wide,” and “have arrested every friend to government on the continent and held them as hostages for the poor victims in Boston.”

Circulation by the enemy of these statements sank all hopes of diplomacy. After that episode, Abigail resumed signing letters “Portia.”

Through eight months of siege, Abigail’s updates became steadier and her commentary sharper. “Tis only in my night visions that I know anything about you,” she wrote October 21, needling John for his laggard epistolary ways but also reporting a wide range of goings-on around Boston. A wood shortage meant bakers would only be able to work for a fortnight. Biscuits had shrunk in size by half. The British were constructing a fort near the docks, and the Continental Army was short on provisions.

In that letter, Abigail also commented on Dr. Benjamin Church, a supposed patriot who had been caught passing coded information about the forces surrounding Boston to the British. Locked up by Washington’s men, Church had been dumped as the Continental Army’s “Director General” of medicine and was awaiting arraignment. “It is a matter of great speculation what will be [Church’s] punishment,” Abigail wrote. “The people are much enraged against him. If he is set at liberty, even after he has received a severe punishment I do not think he will be safe.”

Abigail was in mourning. Her mother, Elizabeth Quincy Smith, had died in Weymouth October 1. In his grief, Abigail’s father, Parson William Smith, had lost “as much flesh as if he had been sick,” she wrote, adding that her sister Betsy looked “broke and worn with grief.” She regretted John’s chronic absences, estimating that in 12 years of marriage, they had only actually been together six.

Washington’s troops quietly ringed Boston in a martial noose, placing cannons on high ground that forced the British to depart by sea at the end of March 1776. The warships and transports that carried the enemy away, Abigail wrote on March 17, amounted to the “largest fleet ever seen in America;” she likened the bristle of masts and billows of sails to a forest. Washington allowed Howe’s men to leave unmolested on the proviso that the Redcoats not burn the city. The foe was as good as his word, though some Britons looted like pirates on holiday. Dirty tactics notwithstanding, though, their exit thrilled locals, Loyalists excepted.

Abigail told John she felt the burden of the British presence merely to be changing location but admitted to being happy that Boston had not been totally destroyed. The city’s escape exhilarated John, a fiend for independence. On March 29, he wrote to Abigail about his joy at learning Boston was free, even as he moped that he knew few details and so awaited her accounts with “great impatience.” He wanted Boston Harbor made impregnable. Abigail had neither the ability nor the desire to command troops, but John often discussed strategic ideas with her and greatly valued her opinion of them.

Most of the time.

The most famous look into Abigail’s politics arose from Patriot celebrations of the British retreat. Abigail only reminded John that he “Remember the Ladies” after she had unleashed a condemnation of Virginia. “I have sometimes been ready to think that the passion for liberty cannot be equally strong in the breasts of those who have been accustomed to deprive their fellow creatures of theirs,” she wrote March 31, 1776. “Of this I am certain that it is not founded upon that generous and Christian principle of doing to others as we would that others should do unto us.”

The letter gained fame because in it Abigail forcefully characterizes women’s second-class status in the colonies. Law and custom barred women from owning property and assigned any wages they earned legally to their husbands. “All men would be tyrants if they could,” and if a Declaration of Independence was coming, it would be shrewd not to put all of the power in the hands of one sex, Abigail argued.

She dusted her broadside with drollery. “The ladies,” she said, were prepared “to mount a rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any laws in which we have no voice, or representation.” The letter also conveyed notes of optimism, originating as it did in one finally assured she could plant seeds on her farm or go for a walk without hearing cannonades.

But that optimism evaporated. John dismissed his wife’s adjuration to “Remember the Ladies.” In an April 14 note, he pooh-poohed Abigail’s thoughts as “saucy”—implying that she was straying from her designated societal role and venturing into arenas she should eschew. John’s shrugging response irked his wife. She wrote to Mercy Otis Warren asking if they should compose another appeal to Congress. Frustrated with John’s lackadaisical mien, she and the family faced a stout new challenge just as the absent man of the house was taking on unprecedented responsibilities in Philadelphia.

Smallpox had been blistering indigenes and colonizers in disfiguring, deadly waves around North America since the Europeans first arrived. In 1775-76, British occupiers and Continental Army soldiers besieging them loosed a particularly severe outbreak. Abigail first mentioned the pox in her March 17, 1776, letter to John celebrating the city’s survival. As the British were withdrawing, the port was still battling the latest epidemic. Only the previously infected were even being allowed into town, a category that would have included John Adams, who in 1764 had undergone a controversial procedure—inoculation.

To inoculate against the pox, a doctor opened a small wound and into that cut or scrape inserted matter intentionally tainted with exudate from a person with smallpox. The idea was to trigger a mild case of pox from which the recipient emerged in a few weeks enjoying lifelong immunity, as occurred with survivors of full-on cases like George Washington. By summer 1776, inoculation had become en vogue. The “Spirit of Inoculation,” as Abigail labeled it, finally achieved such critical mass that city authorities legalized the procedure.

Writing on Sunday, July 7, Abigail invited John Thaxter, who was her cousin and John’s law clerk, to “come have the small pox with my family” that Thursday, July 12. As a clinical setting Abigail’s cousin Isaac Smith Sr. provided his sprawling Boston home. Abigail, Thaxter, the Adams children, and nearly 20 others, including Abigail’s sister Betsy Smith Cranch and her family, as well as strangers like Becky Peck, crammed the mansion to await inoculation by Dr. Thomas Bulfinch. The doctor was charging 18 shillings per week for what he estimated would be three weeks of sequestration while inoculation did its work. During that time those inoculated could expect to experience smallpox symptoms to a greater or lesser degree.

The next day, Abigail wrote her first letter to John since June 17. The children had undergone inoculation “manfully,” she reported. She wished John could have joined them, she wrote, but the opportunity had arisen on short notice, and most residences around Boston were at and beyond capacity. The group had been lucky to book a house.

That year’s hot summer would have had the city resonating around the clock with coughing and the house redolent of rotting flesh—two noxious and prominent smallpox symptoms. Abigail wrote that the children “puke every morning,” complaining to John that a maid she had hired was useless, the girl’s lone qualification being immunity conveyed by a case of the pox.

Owing to a leisurely postal system Abigail’s graphic letter about those events was not the means by which John learned his family had been inoculated. Letters reporting the coup from Isaac Smith Sr. and young Boston attorney Jonathan Mason reached Philadelphia first, stunning John. In a letter to Abigail dated July 16, beset by worry that colleagues would think him a cad for ignoring his loved ones in their hour of need, he poured out his heart. His feelings were “not possible for me to describe, nor for you to conceive my feelings upon this occasion.” He remained steadfast in his commitment to press on with the Congress. “I can do no more than wish and pray for your health, and that of the children,” he wrote. “Never—never in my whole Life, had I so many cares upon my Mind at once […] I am very anxious about supplying you with money. Spare for nothing, if you can get friends to lend it to you. I will repay with gratitude as well as interest, any sum that you may borrow.”

Abigail’s letter of July 13-14 arrived July 23. By then, the effects of inoculation had begun to take hold. Abigail experienced only one “eruption”—a pustule signaling infection. Nabby and John Quincy had gotten sick, but without eruptions. Thomas and Charles showed no symptoms, so she had them re-inoculated. Around this time, she got her first intimate look at the real disease. On July 29, she wrote, fellow inoculant and temporary housemate Becky Peck had symptoms of smallpox “to such a degree as to be blind with one eye, swelled prodigiously, I believe she has ten thousand [pustules]. She is really an object to look at.”

Lags between letters consigned John to anticipating past events. He wrote that Abigail’s accounts had convinced him that Charles had not yet taken the smallpox virus. By the time that news reached Abigail, she had had Charles inoculated a third time, and Nabby a second. Hundreds of pea-sized pustules covered almost all of Nabby’s body. In one letter, John referred to her as his “speckled beauty.” Abigail’s ordeal ground on until September 4, 1776, when she and Charles returned to Braintree. A treatment advertised as lasting three weeks had stretched into seven.

During her siege by inoculation, Abigail occasionally slipped away briefly. She left the family lodgings on July 18 to attend the first public reading of the Declaration of Independence. She stood in a large crowd below the balcony of the Massachusetts State House on Boston’s King Street to listen to the words her husband and his committee had helped draft. Writing to John she described a scene of great joy punctuated by church bells and celebratory gunfire. She, however, attended the fete in a state of disappointment.

In her July 14 letter, Abigail had reacted sourly to a rendering of the finished declaration that John, copying it himself, had sent. “I cannot but feel sorry that some of the most manly sentiments in the Declaration are expunged from the printed copy,” she wrote. “Perhaps wise reasons induced it.” She likely meant an earlier draft Thomas Jefferson had written and shown to John. That version denounced slavery, a sentiment expunged from the version made public. It is reasonable to hypothesize that, reading the version in her husband’s handwriting, Abigail thought that John had composed the entire document and that he himself had eliminated the statement on slavery.

During the inoculation interlude, Abigail was on tenterhooks anticipating John’s return; he had asked her to direct a man with two horses to fetch him in Philadelphia. However, on June 12, John was named president of a new Committee on War and Ordinance, recasting him as a one-man defense department in charge of organizing a military, allocating that force’s finances, supplying Washington’s men, and more. Just as Abigail was preparing to return home to Braintree from the Smith house, John intuited that New York City was to be the war’s next battleground. He would have to stay in Philadelphia to nurse the infant country he had just helped found. Often in correspondence he fretted about his health.

In Braintree Abigail struggled. Farm workers were scarce. Most men had enlisted in the Army, taken up privateering, or, as Loyalists, had fled with fellow Tories. Tea, which soothed her headaches, was at least as scarce as farmhands; John did send a tin that the courier delivered to Elizabeth Adams, his second cousin Samuel’s wife.

In November 1776 John escaped the revolution’s gravitational pull and joined his family for their first significant reunion since April 1775. The children had survived. He and Abigail had gained the independence they had sought together for years. Abigail had been the keystone, communicating crucial information to the Congress, guiding the household through smallpox, and uplifting John through good times and bad. Always appreciative of his spouse’s integral part in his public life, he wrote of his feelings for her to a friend the day after he had signed the Declaration. “In times as turbulent as these, commend me to the ladies for historiographers,” John Adams wrote July 5, 1776. “The gentlemen are too much engaged in action. The ladies are cooler spectators….There is a lady at the foot of Penn’s Hill, who obliges me, from time to time with clearer and fuller intelligence, than I can get from a whole committee of gentlemen.”

Jon Mael is a high school teacher and author from Sharon, Mass. He has been fascinated by Abigail Adams for decades. Follow him on Twitter @jmael2010.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.